Doing What I Can't

“The greatest teacher, failure is.”

When Buster Keaton stepped from a real world stage onto a projector screen in Sherlock Jr., it was a revolutionary moment in the history of cinema. Although the effect was accomplished with a simple jump cut, it was the seemingly impossible precision of the frames that blew audiences’ minds in 1924. It still blows my mind, nearly a century later. Since being awestruck by the timeless nature of that effect, I have always wanted to provide an audience with that same feeling of wonderment.

To be a skilled entertainer, actor, and filmmaker, Keaton had to be well versed in each element that went into his work — from directing, to stunts, to editing. He was the main ingredient in all of his productions. Early on, I took solace in and inspiration from this; when I was starting out, I was all I had. Over the years, I feel that I have developed a love, or at least a fearful respect, for every job on set. Even now, I frequently find myself being the main creative force behind the camera, and in front of in most of my films (even if the latter is out of necessity).

For Keaton, even more important than being a jack of all trades, was simply being willing to fail. He was notorious for demanding dozens of takes, until the shot was just right, and would put it all on the line every time. In fact, he was so willing to fail that he ended up breaking his neck on the shooting of Sherlock Jr — although, he wouldn’t learn of this fact until a doctor’s appointment many years later.

The importance of failure would be something I would also learn years later and, ironically, would play a key part in my future successes.

I’m grateful that I discovered my passion so early on, as it has enabled me to really work at something fulfilling over a long period of time. When I made a music video with my middle school drama teacher in sixth grade, I never thought that I would end up working with him three years later on a 48 Hour Film Festival. Much less that we would become finalists. What I’ve learned over the years about my process — and my identity as an artist, by proxy — is that each of my creative endeavors acts as a spring-board, pushing me towards not only my next project but towards personal development.

The correlation between project and personal development was often a give and take for me. Heading into uncharted territory would often necessitate going one step forward and two steps back. This paradigm would ultimately result in the biggest failure of my professional career thus far:

I typed the wrong date.

Admittedly, this anecdote is physically painful to relive, as it was my first time working as an editor with a full fledged film crew. Initially, I had high expectations for myself, which began to dwindle with each coming setback. The 48 Hour Film Festival is the most grueling, intense experience a filmmaker could possibly imagine. When anything goes wrong on set, the frustration is magnified by the reality that valuable time has just been lost.

It had been decided that “Dignity”, our short, would be filmed in an elaborate (faked) one-take shot. Working with the director, I isolated patches of the set that were dark enough to act as cut points. As we transitioned between shots, the camera would stop and start in the darkness, so the cut was nonexistent. In the editing room, the crew watched in awe at the nine minute “oner” that we had pulled off. Everyone was all smiles, until a horrifying realization dawned on me.

The submission length limit was seven minutes.

In that moment, all I remembered thinking was that the whole production would be dead on arrival. The film’s tension was anchored in its long pauses, its slow fades, its uncut glory. Moreover, there was no way to cut around shots that are from one angle. I sat pondering this predicament late into a Saturday night. Our submission was due the next day.

I fought the sweet lure of sleep that entire night, trimming bits and pieces, pulling out tiny parts, putting a voice over here, a fade to black there. By morning, I had gotten it down to seven minutes. Even though Roderick Smith brought the bagels, I was the crew’s hero that day. In their eyes, I had saved the film. Little did they know, I would also unwittingly compromise the entire production. It was mid afternoon, several hours before the submission deadline, when I was putting together the opening title crawl. Although I wasn’t going to admit it to myself, my sleep deprivation had fully set in and I was operating at maybe 22% brain functionality. That is how I managed to erroneously type the date as 2016, and also how I managed to miss my mistake before hitting export.

Sounds like no big deal, right? Who cares that it said 8/12/16 instead of 8/12/17? Well, as it turns out, the judges at the 48 Hour Film Festival cared, because we were flagged for disqualification. For all intents and purposes, it read as if we trying to fraudulently submit a movie from the year before. Whoops.

After dropping off the film for submission, I blissfully returned home and began to watch “Dignity” one more time, and as I did, my heart sank. As soon as I noticed the date, I called the people at the 48 Hour Film Festival, terrified that we would be disqualified. Fortunately, I was able to explain the situation to them. Unfortunately, I was not able to get the date fixed before the premiere, and my mistake was all the more visible on the big screen — for a packed audience, of course.

Who was the imbecile that forgot what year it was?

I imagine many might take almost singlehandedly derailing an entire production as a sign that the path of filmmaking wasn’t for them, but not me. This only served to galvanize me on my road to redemption. Little did I know, many more failures would be in store for me. Unfortunately, I had yet to come to terms with the value of failure in the learning process.

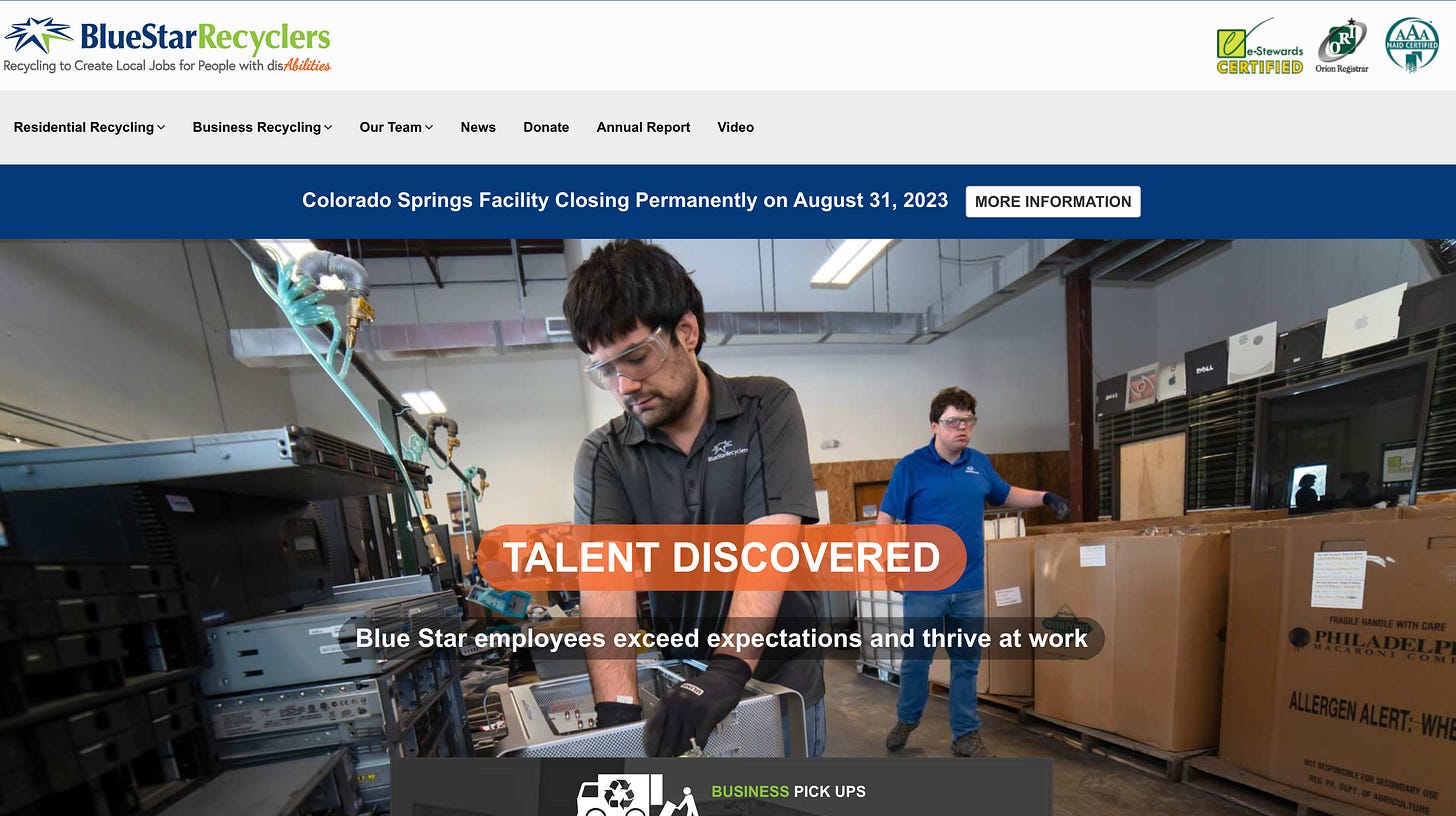

Throughout high school, I worked with a local nonprofit named Blue Star Recycling, a company that employs people on the autism spectrum in the disassembling and sorting of technology for further recycling. I acted as their “social media campaign manager”. Full disclosure: I wasn’t sure how to do what was being asked of me, let alone what the title meant. All of the employees were gracious with their time and patience as I fumbled with a camera I didn’t know how to use, put all the wrong fonts on the banners — needless to say, I failed in nearly every facet.

Nevertheless, I eventually managed to design a website and videos that highlighted the tremendously impactful work that Blue Star was doing. After working alongside these employees over the next couple years, I gained an immense amount of respect concerning the aptitude for careful, detailed, repetitive work that those on the autism spectrum possess. While I am not on the spectrum, myself, I have severe ADHD. Working with these employees was truly a formative experience for me. Growing up, I had always struggled with nuanced tasks and repetition. I am clearly not a detail oriented person — as evidenced by the 48 Hour Film Festival debacle. I had a lot to learn from these guys.

In retrospect, it is astonishing the degree to which those couple of years has informed my current work as an animator at USC. Working frame by frame is the absolute embodiment of detailed repetition and I honestly don’t believe I would have the capacity or patience for it, had I not worked alongside true professionals — who were much more patient and meticulous than I.

Nevertheless, I had yet to make something that I felt was authentically my own. This would come in the form of another happy accident. I found my creative style and sensibilities, strangely enough, shooting commercials for a plastic surgery company, Center For Aesthetics. Dr. Durboraw, my employer, told me I was hired “to make her look cool”. I don’t know if I ever managed that. In fact, I think it is safe to say I did in no way succeed in that endeavor. However, I always did my best to push the envelope and give her something unexpected. One such idea was duplicating Dr. Durboraw in a scene as both patient and doctor.

Unfortunately, Dr. Durboraw pushed back on a lot of the more out-of-the box ideas. We ended up compromising on so much that I couldn’t help but feel that I had failed yet again. However, this time was different. While I may not have been able to execute my vision, I had finally discovered my niche: a synthesis of live action and visual effects. This marked an inflection point in my creative aspirations and there was no going back.

The floodgates were open.

The goal of this project was to fully realize the spirit of the title: “Think Outside Of The Box”. This creative thinking was applied in every facet, from the first person POV, to the scene transitions, to the stunt work, to the soundtrack. I wanted to create something unlike anything I had before.

With my short film “9 More Minutes”, I endeavored to create an elaborate dream sequence, shot in two different states, in two different seasons, but attempted to blend them together as if they were one (channeling my inner Keaton).

I wanted to show how riding a Boosted Board can make any commute feel extraordinarily. To highlight the speed of the Boosted skateboard, I combined long-exposure and stop motion techniques to create the swirling light effects. I opted to compose the soundtrack by sampling the Boosted Board's motor's iconic acceleration sound, using it to build tension in the track.

These were early efforts and looking back, admittedly, the cracks start to show. Nevertheless, these pieces were crucial in the development of my sensibilities as an artist. Moreover, I find charm in these earlier works. Looking back shows me how far I’ve come. These are where I started striving to surprise. My videos began attempting to play off expectation, anticipation and release, in order to deliver something unpredictable. Now, as I try to cultivate range as a digital artist, I’m always inspired by what I can’t do.

A more recent work “Atlantis”, where I have fully delved into the animated space to create something otherworldly.

Before I discovered this visually altered bent of filmmaking, my outlandish ideas were just that, ideas. But as I began to dip my toes into the waters of animation and compositing, new doors opened for me, enabling others to see the world the way I see it. Honestly, there is nothing that makes me more fulfilled than staying up until the break of dawn, arranging clip after clip, frame after frame, to make my vision a reality. Editing for me is so magical because I can accomplish anything with enough time and the right idea. I just might have to fail a few hundred times first.